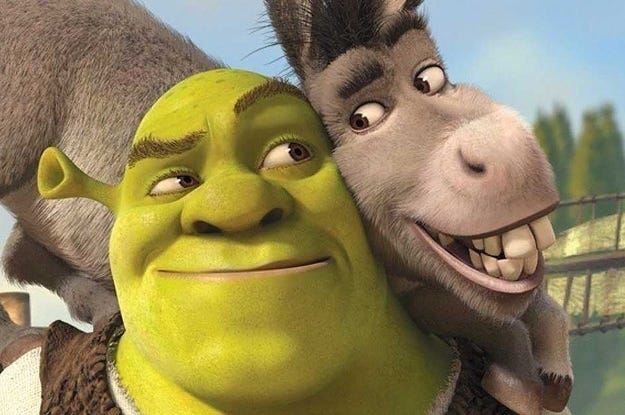

Three years ago, we had friends over on Easter to eat pizza and watch Shrek.

It might not seem like the most obvious resurrection ritual, but I'm here to convince you that that Shrek is a resurrection movie.

Stick with me.

Yes, there is the rolling away of a large stone from the mouth of a cave where a transformation has taken place…

But it's deeper than that.

Shrek is about the incorrect assumption that once you have control over the fundamentally uncontrollable - your body and your community - then you will finally be happy.

Shrek is about people who are not just ostracized, but imprisoned and forcibly relocated for looking different, sounding different, or living in bodies that function differently.

Shrek is about what we find truly grotesque: Is it people who look so different that we've decided they're ugly? Or is it people who abuse their own power, fear the different, and sow rejection?

Shrek is about disability.

Fiona, our leading lady, is cursed and locked away in a tower. We come to find out it's because she turns into an ogre at night. So already we've got parents who hide their child away for being different…

Fiona is shocked to discover that the only people who have been able to successfully retrieve her from her tower are a fellow ogre and his donkey. She expects a handsome prince and noble steed. She has internalized the belief that there is something wrong about herself because of her "ugliness" or "grotesqueness," and therefore those who share those traits must also be lesser, despite their obviously exceptional abilities.

Fiona hides her nightly transfigurations and falls in love with Shrek precisely because he seems to her to have embraced the fact that he can't be anything other than an ogre. But Shrek also struggles with internalized self-hatred alongside some forms of self-acceptance. Shrek teaches Fiona that she is interesting for reasons beyond her looks. Fiona teaches Shrek that looks are not automatically moral.

After a brief but, in my opinion, one of the least infuriating and most effective uses of the miscommunication trope - set to the heart-wrenching and frankly generation-defining rendition of “Hallelujah” by Rufus Wainwright - Shrek confronts Fiona as she’s moments away from marrying the evil villain (who himself, it should be noted, has a physical difference. The movie stops short of drawing the obvious connection between Lord Farquaad's height and his hatred of fairytale creatures - his stand-in scapegoats of his own bodily insecurity and self-rejection.)

As Fiona chooses Shrek and reveals to him her ogre form, she is stunned to find that true love's kiss renders her an ogre permanently. She says, “I was supposed to be beautiful,” and Shrek affirms that she already is.

But that’s also not what the words of the spell actually said.

True love’s kiss was to make Fiona “take love’s true form.” Love’s true form is the form that embraces oneself.

Moral virtue - which many philosophers and theologians throughout history have said is reflected through beauty - is actually entirely unrelated to physical appearance. This can be uncomfortable for students and scholars of theological aesthetics who assert that there must be some sort of objective physical quality of beauty that distinguishes a beautiful thing from an ugly one.

It is not a subjective sense of beauty plaguing the conversation, but a presumed objective sense of morality. We still insist that physical difference is bad, so we continue to see physical difference as ugly.

Fiona and Shrek are no less good, no less beautiful, and no less truly themselves for being "ugly." And so, they are not actually ugly at all.

It is the "handsome" and "heroic" who are ugly - as we continue to learn in Shrek 2. This is part of what makes the sequel just as compelling as the original. In addition to yet another generation-defining cover of an iconic song at the movie's climax - this time “Holding Out for a Hero” - Shrek 2 continues to explore the relationship between beauty and goodness, this time firmly within the context of familial expectations.

Fiona is relentlessly pursued by Prince Charming, who is favored by her parents for being conventionally beautiful but is slimy and immature. Shrek and Fiona both have the chance to become conventionally beautiful at the expense of the virtues that hold their relationship together: honesty, intimacy, and bravery.

In this way, Shrek is a deeply Christian film. Despite the rumors1 that those who worked on the film were being punished in some way by DreamWorks, whose concurrent project was The Prince of Egypt, I think in reality both projects ended up being theological heavyweights.

The core proposal in Nancy Eiesland's seminal text on disability theology, The Disabled God, is that Christ Himself is God disabled. That Jesus is disfigured and wounded during the stations of the cross and the crucifixion, but then resurrects with his wounds intact, suggests something crucial and powerful about the nature of injury, illness, disability, and bodily difference: Coupled with Jesus' prioritizing of the disabled in his healing ministry, it is clear that bodily difference does not disqualify a person from the Kingdom of God, on earth or in Heaven.

Today is Easter, the conclusion of the Triduum: Passion, Death, Resurrection. The Triduum is a story about the B/body. We break bread-which-is-body, wash each other’s feet, watch a man become disabled and killed by the police state, and then witness that same body overcome all of those things and carry onward with and for his community.

Next week, on Divine Mercy Sunday, we’ll hear the story of “Doubting Thomas.” In Christ's revealing of himself to Thomas, who goes so far as to touch Jesus' wounds, the world comes to know Jesus is truly risen not because he says so, but because his body shows so. We know Jesus because his body is broken.

In Shrek 2, Fiona recognizes Shrek, even transformed into a different body entirely, because of the personality revealed by his actions. And in the original film, far beyond Fiona turning into a human at the altar and Shrek loving her despite her difference, Fiona remaining an ogre reveals to the audience that difference is not just something to be overcome, but a necessary asset to our understanding of selfhood and goodness. Shrek loves Fiona within her bodily difference.

If we the audience are momentarily disappointed by Fiona's green ears emerging from the bright, transfiguring light, we are revealing to ourselves that we still believe there is something lost by being in a different kind of body. We are in the chapel audience laughing with Lord Farquaad at her hideousness. To the very end, we are being taught a lesson that seemed to need a second movie with a nearly identical theme for us to really get it…

And frankly, we’re still not getting it.

RFK Jr. has officially launched his war on autism.

The Right uses language of “disease” and “epidemic” to describe autism diagnosis, which entirely mischaracterizes the nature of neurological, mental, and physical difference. This language is designed to encourage us to believe without question that the elimination of bodily difference - disabilities both acquired and congenital - is a no-brainer. It’s eugenics. Eugenics is defined as the belief that not only are certain kinds of bodies more valuable than others, but that bodily difference poses a threat to society in some way.

A disabled body is no “less” than any other kind of body. Neurological difference is just that: Difference, not deficiency. And in fact, all people are going to experience disability in their life. Every single one. If you are lucky enough to live a long, conventionally healthy life, aging will disable you, both physically and mentally.

Disability is not a type of body, it’s a universal experience of the body that simply occurs differently in different people.

Certainly, this difference can occur at various degrees of severity. Disability impacts peoples’ quality of life in more or less painful or accommodating ways. Some people may in fact want their disability to be eradicated and may perceive themselves as separate from their disability. Other people see themselves as fully themselves because of their disability, and the eradication of their diagnosis means death.

The “solution” to autism - or to any disability - is not to pathologize but to invest.

We must invest in resources that accommodate and include people with disabilities. We must invest time in listening to disabled persons and their loved ones, to listen to what they actually need, not what would make us more comfortable in being around them.

Now more than ever, disability theology is a crucial endeavor. As the Right is increasingly motivated by a limited view of Christianity, informed by their own agenda and then twisted to match it, the truth of disability revealed by the most pivotal moments of the Christian faith must be protected and amplified.

This is why I started Theology for Every Body. You can learn more about that project below:

It's Easter, and I’m thinking about Shrek. When we invited our friends over years ago, I hadn’t made any of these connections at all. We’d been talking about Shrek at a party and decided Easter was as good a time as any for a rewatch.

But now, as the film only gets better with age, as we watch the current political moment turn its attention to embodied difference (as fascism always does, and which I’m going to write even more about soon) - and as we await confirmation that the animators of the forthcoming Shrek 5 might listen to audience outrage and change the animation style back - I think watching Shrek might have to be a yearly Easter tradition.

I find it interesting that the URL for the New York Post article on this rumor is “ugly-green-montrous” [sic] even though that has nothing to do with the content of the article